Andrea Martinez-Noya, Esteban Garcia-Canal, Mauro F. Guillen

We combine the streams of literature on outsourcing and offshoring to investigate (1) whether choosing an R&D offshore outsourcing strategy by technological firms is advisable, and (2) where these firms are more likely to allocate these R&D services outsourcing agreements offshore, namely, in developed or developing economies. Using original survey data from European and U.S. firms in technology-intensive industries, we place especial emphasis on the fact that certain firm-specific capabilities, such as technological and international expertise, are required in order to outsource R&D overseas, especially when offshoring to developing economies, as transaction costs are still the main deterrent to outsource offshore to these regions. In addition, our results also show that in the specific case of R&D services outsourcing, knowledge-seeking objectives lead to outsource to developed economies.

1. Introduction

Research has documented that firms are changing their sourcing strategies in two ways. First, they are increasing the range of activities along the value chain that are outsourced (Gilley & Rasheed, 2000; Hätonen & Eriksson, 2009; Hitt, Keats, & De Marie, 1998; Jacobides, 2005; Kotabe & Murray, 2004; Quinn & Hilmer, 1994) including areas that were traditionally vertically integrated, such as those related to the innovation process (Cesaroni, 2004; Gooroochurn & Hanley, 2007; Granstrand, Patel, & Pavitt, 1997; Howells, Gagliardi, & Malik, 2008; Leiblein, Reuer, & Dalsace, 2002; Manning, Massini, & Lewin, 2008; Narula, 2001; Quinn, 2000; Subramaniam & Venkatraman, 2001; Tsai & Wang, 2009; UNCTAD, 2005; Veugelers, 1997). Second, firms are increasingly outsourcing innovating activities offshore, not only to providers located in developed countries but also to those in developing ones (Bunyaratavej, Hahn, & Doh, 2007; Doh, 2005; Dossani & Kenney, 2007; Javalgi, Dixit, & Scherer, 2009; Jensen, 2009; Kedia & Mukherjee, 2009; Kotabe & Mudambi, 2009; Mol, Pauwels, Matthyssens, & Quintens, 2004; Mol, van Tulder, & Beije, 2005; Un, 2009).

As a consequence, the R&D function is being disintegrated into different technologically separable R&D services (Fosfuri & Roca, 2002; Gottfredson et al., 2005; Howells et al., 2008) that can be performed in different locations either by the firm or by an external contractor (Arora & Gambardella, 2005; Hirshfeld & Schmid, 2005; Levy, 2005; Lewin & Peeters, 2006; Lewin, Massini, & Peeters, 2009; Manning, Massini & Lewin, 2008; Maskell, Pedersen, Petersen, & Dick-Nielsen, 2007). Therefore, firms need to search for the optimal governance (outsourcing versus internal development) and geographical location (offshoring versus domestic) of each of the activities or R&D services within their value chain.

Even though these two decisions are closely related, the scarce existing research dealing simultaneously with both decisions is either theoretical (Contractor et al., 2010; Doh, 2005; Graf & Mudambi, 2005; Hätonen & Eriksson, 2009; Kedia & Mukherjee, 2009; Martínez-Noya & García-Canal, 2011a; Mudambi & Tallman, 2010) or case oriented (Hätönen, 2009; Mudambi & Venzin, 2010). On the one hand, empirical studies analyzing the R&D outsourcing decisions by technological firms tended to overlook the location dimension (Afuah, 2001; Hitt et al., 1998; Leiblein & Miller, 2003; Mayer & Salomon, 2006; Mol, 2005; Narula, 2001; Pisano, 1990; Veugelers & Cassiman, 1999). On the other, those studies more focused on the location decision either tended to analyze only FDI or internal modes of governance (captive offshoring) (Belderbos, 2001; Berry, 2006; Bunyaratavej et al., 2007; Cantwell, 1995; Demirbag & Glaister, 2010; Doh, Bunyaratavej, & Hahn, 2009; Kuemmerle, 1999; Odagiri & Yasuda, 1996; Piscitello & Santangelo, 2010; von Zedwitz & Gassmann, 2002) or to analyze the offshoring phenomenon in the aggregate without distinguishing between internal (captive offshoring) and external (outsource offshoring) modes of governance (Dossani & Kenney, 2003; Lewin & Couto, 2007; Lewin et al., 2009; Manning et al., 2008; Mudambi, 2008).

In order to close this gap in the IB literature, this paper combines these streams of literature on outsourcing and offshoring and elaborates on the factors that drive technological firms to outsource R&D services offshore and to a particular offshore location. In particular, given the recent evidence on the rise of offshoring of innovative activities and advanced services to developing economies, this paper aims to contribute to this literature by analyzing the factors driving these firms to locate their R&D offshore outsourcing agreements in a developing economy versus a developed one. Although it is known that greater enforceability of contracts overseas has allowed for the increasing dispersion of these agreements (Narula & Hagedoorn, 1999), there is, to the best of our knowledge, little empirical evidence explicitly analyzing the determining factors of the location of offshore R&D outsourcing agreements. Some exceptions can be found that explicitly analyze international outsourcing of technical work or other advanced services, however, they do not differentiate between offshore outsourcing locations (Chen, 2004; Griffith et al., 2009; Martínez- Noya & García-Canal, 2011b; Mol et al., 2005; Quinn & Hilmer, 1994). Analyzing jointly whether and where to outsource is important not only for theoretical reasons, but also because the offshoring decision, like other strategic choices, is subject to endogeneity and self-selection (Shaver, 1998). In addition, this research question is not only of interest from a managerial perspective but also from an economic policy perspective. Indeed, recent studies argue that firms are increasingly relocating innovation activities to developing countries because of the highly qualified workforce within these regions (Lewin et al., 2009; Manning et al., 2008). Thus, given the fiscal and non-fiscal instruments that both developed economies and developing ones may employ to stimulate investments in R&D (Mani, 2004), governments from developed economies actually need to proactively attract these value-added services by fostering local infrastructure and their National Systems of Innovation. However, identifying what R&D government policies may be more effective to attract R&D outsourcing contracts from foreign firms, as well as to help to avoid local firms outsourcing offshore (Lieberman, 2004) calls for a better understanding of these practices.

Therefore, combining insights from the resource-based view and transaction cost theory, we argue that, while the probability of technological firms outsourcing R&D services offshore will be mainly determined by firms’ characteristics such as the possession of technological resources and capabilities, together with their international experience, their preference for a developing versus a developed location will mainly be determined by the firms’ motives for outsourcing the R&D service and the attributes of the R&D service outsourced. We find support for these hypotheses using original survey data on R&D outsourcing practices by 182 technology-intensive firms from the U.S. and the European Union. Although some of these factors have already been used in previous research on outsourcing or offshoring, their influence has not yet been tested in the context of whether and where to offshore R&D services. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first quantitative study providing evidence on both the organizational and geographical dimensions of R&D offshoring. Specifically, this study contributes to this literature by showing that certain managerial capabilities are required in order to outsource R&D services overseas, especially when offshoring to developing economies, as transaction costs are still the main deterrent to outsource offshore to these regions.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we review previous literature on R&D outsourcing and offshoring decisions, and we develop our theoretical model and hypotheses. In Section 3, we describe the data and our research methods. In Section 4, we report the results. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of the contributions, limitations, directions for future research, as well as with managerial and policy implications of our study.

2. Theoretical background

When organizing their R&D value chain, firms face several decisions such as how to source each R&D service—i.e. the outsourcing decision—and where to locate it—i.e. the offshoring decision. Whether or not the outsourcing decision precedes the offshoring one is subject to debate (Contractor et al., 2010; Doh, 2005; Graf & Mudambi, 2005; Hätönen, 2009; Hätonen & Eriksson, 2009; Kedia & Mukherjee, 2009; Mudambi & Tallman, 2010; Mudambi & Venzin, 2010), and goes beyond the scope of this paper. Whatever the case may be, four different sourcing strategies for each R&D service can be identified: (1) to perform it in-house in its home country, (2) to outsource it to a provider in its home country, (3) to perform the R&D service in-house but under an affiliated foreign subsidiary (what is called captive offshoring) or (4) to outsource the R&D service to an unaffiliated provider located in a foreign country (what is called offshore outsourcing).

In order to analyze whether and where to pursue R&D offshore outsourcing, we largely draw from the resource-based view and transaction cost theory. According to the resource-based view, firms establish outsourcing agreements searching for complementary resources and/or capabilities that are not available within the firm (Agyres, 1996; Barney, 1991; Grant, 1996; Peteraf, 1993; Quinn & Hilmer, 1994). Therefore, a core capability of technological firms, especially in a changing environment, is the ability to coordinate and integrate their distributed activities along their value chains as well as exploring and exploiting new emerging technologies (Granstrand et al., 1997; Patel and Pavitt, 1997). Firms operating in technology-intensive industries face competitive pressures to build a larger and broader portfolio of related products in order to gain and maintain their competitive advantage, which drive them to rely on outside suppliers in order to organize some R&D services (Leiblein & Miller, 2003; Nicholls- Nixon & Woo, 2003; Quinn, 2000). Specifically, through outsourcing they can concentrate on those parts of the process in which they can exploit their competitive advantage, benefit from more technological solutions, and take consequent advantage of more business opportunities (Cesaroni, 2004). The fact that the knowledge transfers associated to R&D services outsourcing can lead to appropriability hazards (Kogut, 1988; Oxley, 1997) requires combining the insights of resource-based view with those of transaction cost theory, as the conflicts and tensions stemming from these hazards influence not only the decisions regarding whether to outsource or not but also where (Henisz & Williamson, 1999).

Owing to the heterogeneity of resources located around the world, the external resources needed by a firm may not be available within its home country, and these cross-country differences in resource endowment may drive the firm to seek such resources offshore, searching for location-specific advantages (Dunning, 1998). Indeed, research has found that knowledge- intensive firms from both advanced and developing countries are globally dispersing their value chains to control costs and leverage their capabilities (Mudambi, 2008). Therefore, through outsourcing offshore, these firms have found a way not only to be more efficient or flexible, but also to benefit from the distinctive capabilities of a specialized provider located not only in developed economies but also those in developing ones (Chen, 2004; Graf & Mudambi, 2005). Previous research has found that offshore outsourcing is a result of a firms’ ability to search for and evaluate foreign providers (Mol et al., 2005; Rangan, 2000). On a similar vein, Patel and Vega (1999) found that firms invest offshore in core innovative areas where they are strong at home, while Brusoni et al. (2001) stated that firms must know more of what they need for what they make not only to monitor their suppliers but also to be able to efficiently perform the role of systems integrator. In addition, this excess of knowledge will provide them with the absorptive capacity to benefit from external sources of knowledge (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). Therefore, although it can be expected that the firm’s probability to establish R&D outsourcing agreements offshore will be mainly driven by its technological resources and capabilities as well as by its international experience, these hypotheses have yet to be tested on an international sample of R&D services offshore outsourcing practices by technological firms.

With respect to the question of where technological firms are more likely to locate their R&D offshore outsourcing agreements, it has been shown that R&D activities involving highly tacit and complex knowledge are concentrated at the firm’s home country, while the development of less tacit knowledge is more geographically dispersed (Cantwell & Santangelo, 1999). As a result, from a capabilities point of view, and despite the growing globalization of markets, there is still a clear specialization of locations that favors the rise of a market for technologies (Arora, Fosfuri, & Gambardella, 2001). In relation to this, previous literature showed that the main motivation for firms to outsource overseas is the search for location-specific advantages, especially to exploit differences in costs and technological expertise (Ghemawat, 2003). On the one hand, FDI literature on R&D argues that firms may decide to internationalize their R&D activities to a particular location, either to cut costs or to explore or acquire new knowledge (Hagedoorn, 1993; Kuemmerle, 1999; Le Bas & Sierra, 2002; Narula & Hagedoorn, 1999). On the other hand, previous research on offshoring (Hätönen, 2009; Lewin & Peeters, 2006; Manning et al., 2008) highlights the importance of differences in costs and qualification.4 Therefore, some inputs and technical knowledge may be available only in some locations, so that firms may decide to outsource some of their activities from these locations in order to access available technological expertise (Calderini & Scellato, 2005; Cantwell & Santangelo, 1999). While firms located in advanced economies may find that labor costs are high compared with the value added to their products (Kotabe, 1998; Trent & Monczka, 2003) and may therefore decide to outsource some of these activities to low-cost countries in order to reduce costs. With regard to this, recent evidence suggests that firms are increasingly relocating innovation activities to developing countries because of the highly qualified workforce within these regions (Lewin et al., 2009; Manning et al., 2008). However, to the best of our knowledge, previous studies analyzing R&D offshoring to developing economies either just consider captive offshoring decisions (Demirbag & Glaister, 2010; Doh et al., 2009; Piscitello & Santangelo, 2011) or they analyze R&D offshoring in the aggregate, that is, without distinguishing between internal (captive offshoring) and external (offshore outsourcing) modes of governance (Lewin et al., 2009; Manning et al., 2008). Thus, the determining factors of the location of R&D services offshore outsourcing agreements have not been empirically tested yet.

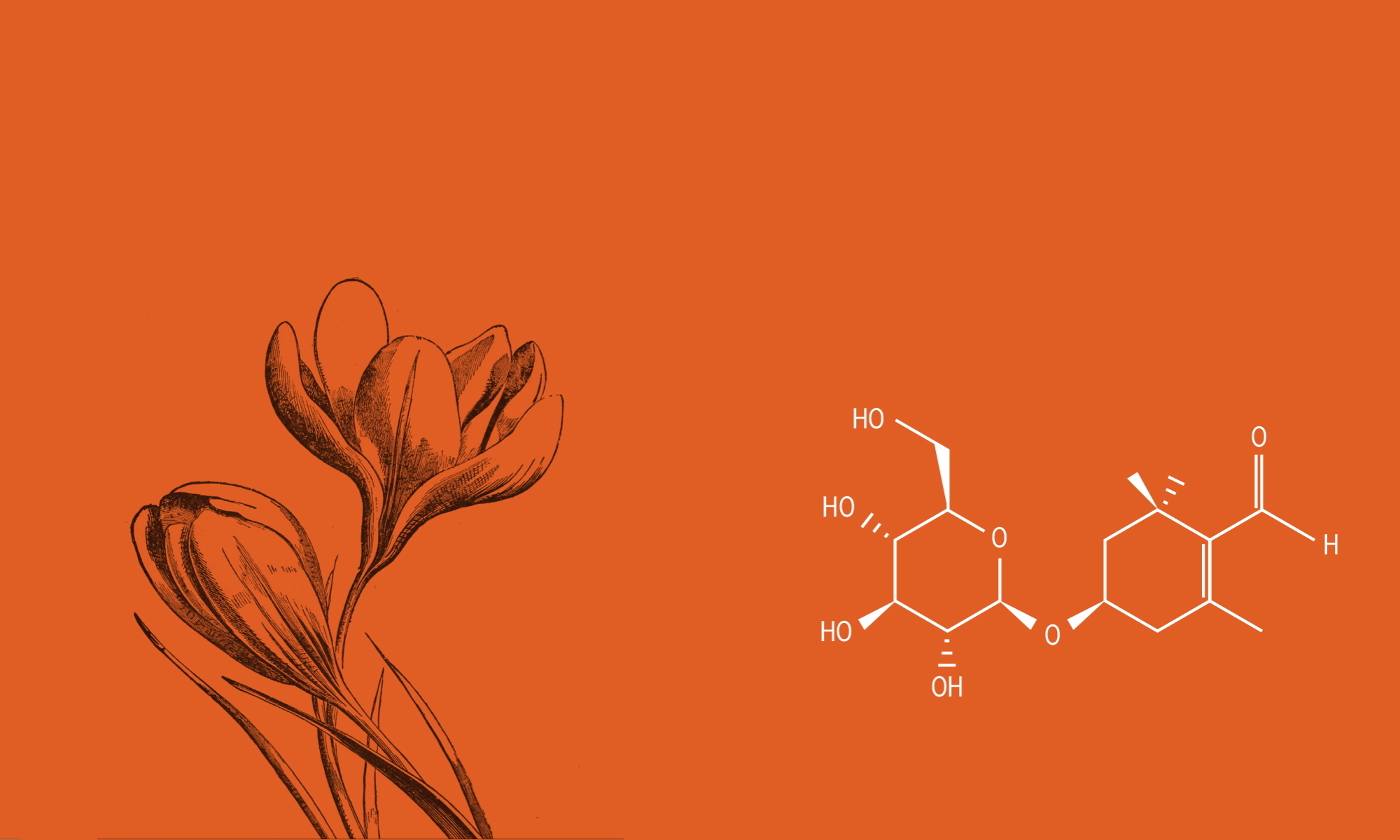

Taking all of these antecedents into account, we develop a framework in which arguing that the probability of these firms outsourcing R&D services offshore will be mainly determined by firms’ characteristics such as the possession of technological resources and capabilities together with their international experience, while the preference for a developing versus a developed location will be mainly determined by firms’ motives for outsourcing the R&D service together with the attributes of the R&D service outsourced. Fig. 1 displays the main hypotheses.

2.1. The decision of whether or not to outsource R&D services offshore

Firms do not possess the same capabilities, especially in the technology area, nor do they have similar levels of international experience. Therefore, not all firms are equally prepared to make the most of the potential benefits of offshore outsourcing (Martínez-Noya & García-Canal, 2011b). Taking all of this into account, we expect that the firm’s probability to establish R&D outsourcing agreements offshore as compared to other sourcing options will be mainly driven by the firm’s degree of accumulation of technological resources and capabilities, and its international experience. These are factors that will determine the firm’s capability to effectively manage, coordinate and integrate these agreements with providers located overseas.

Fig. 1. Theoretical framework.

Fig. 1. Theoretical framework.

2.1.1. Technological resources and capabilities

When it comes to outsourcing R&D services, firms with strong technological capabilities are likely to have an edge over their competitors. Initially, it could be expected that the more technological resources and capabilities a firm has, the less it will need to search for external sources of innovation. However, these capabilities can be leveraged if some specific parts of the R&D process are outsourced to an external entity, that is to say, combining vertical integration and strategic outsourcing—an organizational practice known as “taper integration” (Rothaermel, Hitt, & Jobe, 2006). Due to the complexity of the innovation process, firms cannot achieve the same level of efficiency across all the activities along the process, and thus engage in both integration and outsourcing (Afuah, 2001). Some firms even follow a concurrent sourcing strategy, i.e. they simultaneously make and buy the same good or service (Parmigiani, 2007; Rothaermel et al., 2006). We therefore expect that, besides outsourcing at the domestic level, technology-intensive firms will need to search for efficient ways of relocating and organizing their different R&D services worldwide (Mudambi, 2008). This would imply that, whenever possible, these firms will prefer to outsource their R&D services to best-in-world providers in order to maintain their competitive advantage, either because they are more specialized or because they can perform the task at a lower cost. Therefore, due to the heterogeneity of technological resources across countries, we expect firms with sound technological capabilities to be more likely to outsource R&D services offshore, as they will need to search either for state-of-the-art or low-cost providers. Indeed, these are the kind of providers that allow them to leverage their technological resources whilst maintaining a competitive advantage over their rivals (Un, 2009).

The previous literature has also shown the importance of taking contractual issues into account in governance choices (Banerjee & Duflo, 2000; Metiu, 2006). More specifically, as firms accumulate technological capabilities they will not only be under more pressure to search for world-class suppliers, but also better equipped than other firms to establish outsourcing agreements with foreign providers (Mayer & Salomon, 2006) and to effectively manage a loosely coupled network of external suppliers by performing the role of systems integrator (Brusoni et al., 2001). Therefore, although firms lacking these capabilities would also benefit from global outsourcing, whatever the motive for doing so, they may not have the capability to manage such agreements. Firms lacking adequate technological resources will be ill-equipped to select an appropriate partner, as well as to monitor its performance and will therefore face both adverse selection problems and important moral hazards. Thus, although we expect these governance capabilities to also increase the likelihood of domestic R&D outsourcing, we also expect them to be particularly critical when establishing contractual agreements offshore. In fact, as shown by Tsai and Wang (2009), by collaborating with different types of partners, firms with more internal R&D investment gain higher innovation returns than firms with fewer internal R&D activities. As a consequence, we expect that:

Hypothesis 1. The more technological resources and capabilities the firm possesses, the more likely it will outsource R&D services to offshore providers compared to other organizational alternatives.

2.1.2. International experience

Although not tested in the context of R&D offshore outsourcing, previous research showed that international outsourcing is a result of a firms’ ability to search for and evaluate foreign providers (Mol et al., 2005; Rangan, 2000). Indeed, Rangan’s (2000) study showed that a lack of knowledge leads to the screening out of foreign sources, while a lack of previous interaction increase uncertainty regarding partners’ reliability and fear of opportunistic behavior. With regard to this, firms’ international experience has been considered in the literature as one of the most important sources of organizational learning (Belderbos, 2003; Kogut & Zander, 1993). It has been proved that firms’ foreign subsidiaries may act as a mechanism to access local knowledge and generate new technology (Frost, 2001; Veugelers, 1997), and thus they can contribute to the creation of firm-specific advantages (Birkinshaw, Hood, & Jonsson, 1998). Research has also highlighted the fundamental role that external linkages with other organizations have in the development of subsidiary capabilities, especially on R&D (Frost, Birkinshaw, & Ensign, 2002). For this reason, based on this previous literature, we expect that the likelihood of a firm locating R&D outsourcing agreements offshore will depend not only of its technological capabilities but also of its existing international involvement. This is because, on the one hand, this international experience will allow the firm to better identify and gain access to offshore providers, while on the other hand, these external linkages are expected to contribute to enhance subsidiary capabilities. So, as it happens in relation to firm’s technological capabilities, firms lacking international experience may face severe problems arising from their unawareness of how to operate in those offshore locations. It should be noted that firms may be choosing to outsource R&D services offshore because they do not have enough international experience on how to operate in specific offshore markets. However, even if this is the case, based on the previous arguments, it can be expected that international experience is still required in order to develop the managerial capabilities to effectively establish R&D outsourcing agreements with offshore providers. As a consequence, we expect that:

Hypothesis 2. The more international experience the firm possesses, the more likely it will be to outsource R&D services to offshore providers compared to other organizational alternatives.

2.2. The decision on where to outsource R&D services offshore: developing versus developed countries

When analyzing R&D offshore outsourcing practices, one question that has not been empirically addressed is which factors drive the location of specific R&D services to a particular offshore location. Consistently with the RBV and in line with the theoretical oriented studies on this issue by Graf and Mudambi (2005) and Hätönen (2009) highlighting the primary influence of factors such as what is being outsourced and why, and what kind of experience the firm has, on the decision of where to locate R&D services outsourcing agreements, we expect this location decision to be dependent on: (i) its main motive for outsourcing the R&D service, i.e. knowledge or lower labor cost-seeking; and (ii) the characteristics of the service being outsourced, specifically on its degree of tacitness and on its level of technological uncertainty.

2.2.1. Firms’ motives for outsourcing offshore

It has been proven that the main motivation for firms to outsource overseas is the search for location-specific advantages, especially to exploit differences in costs and technological expertise (Ghemawat, 2003). Indeed, despite the growing globalization of markets, there is still a clear specialization of locations that favored the rise of a market for technologies (Arora et al., 2001). We build our argument on the basis of two lines of research. Firstly, the FDI literature on R&D argues that firms may decide to internationalize their R&D activities either to cut costs or to explore or acquire new knowledge (Hagedoorn, 1993; Kuemmerle, 1999; Le Bas & Sierra, 2002; Narula & Hagedoorn, 1999). Second, and more specifically, recent research on offshoring (Hätönen, 2009; Lewin & Peeters, 2006; Manning et al., 2008) highlighting the importance of differences in costs and qualification as drivers of these decisions.5

2.2.1.1. Knowledge-seeking.

Given that R&D services are knowledge-based activities, and knowledge tends to be location-specific, some locations may offer specialized know-how or capabilities within a specific technological domain (Calderini & Scellato, 2005; Cantwell & Santangelo, 1999). Indeed, it has been shown that a key driver for firms’ geographic distribution of R&D activity is the access to knowledge spillovers (Feinberg & Gupta, 2004; Lahiri, 2010). As a result, in order to tap these resources and access this technological expertise, firms may need to establish outsourcing agreements with providers located within such economies so as to benefit from these specialized providers and take advantage of their experience. As to where these pockets of expertise are located, mixed evidence exists. On the one hand, it has been proven that the majority of high-end product development and engineering activities are still being carried out in advanced Western economies (Disher & Lewin, 2007), basically because world leaders in knowledge and technology are typically located within developed economies (Arora et al., 2001). On the other hand, recent studies argue that innovation activities are increasingly being offshored to developing economies searching for talent, due to the emergence of new geographical technological clusters in developing economies, such as in India or China (Lewin et al., 2009; Manning et al., 2008; Ricart, Agnese, Pisani, & Adegbesan, 2011). Therefore, even if high-value added activities were largely performed in advanced economies, while low value-added ones were performed in developing economies (as stated, among others, by Mudambi, 2008), this location pattern would be under pressure as developing countries upgrade their technological competences and thus more technological advanced activities are being offshored to these economies (Dossani & Kenney, 2007; Jensen, 2009; Maskell et al., 2007). Thus, due to the lack of conclusive results on this issue applied to the specific context of R&D services offshore outsourcing decisions, and the fact that R&D offshore outsourcing is considered as being still at an early stage, we propose two different hypotheses in relation to the preference for a developing versus a developed economy the more important is knowledge-seeking as a reason for outsourcing the R&D service.

On the one hand, because developed economies are usually more technologically advanced, boasting access to better technological infrastructure or centers of excellence, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3a. Conditional on the firm having decided to outsource to an offshore provider, the more important knowledge- seeking is as a motive for outsourcing, the less likely the R&D service is to be located in a developing economy.

On the other hand, due to the recent evidence suggesting that firms are increasingly offshoring innovation activities to developing countries because of their highly qualified workforce and the emergence of specialized pockets of expertise within these regions, we also hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3b. Conditional on the firm having decided to outsource to an offshore provider, the more important knowledge- seeking is as a motive for outsourcing, the more likely the R&D service is to be located in a developing economy.

2.2.1.2. Lower labor costs seeking.

As R&D activities are knowledge-based and in consequence rather labor-intensive, cost remains an important driver of offshore outsourcing, given that some firms within developed economies may find their labor costs high compared with those of developing ones (Javalgi et al., 2009; Kotabe, 1998; Trent & Monczka, 2003). The development of a low- cost market of qualified providers located in developing economies, not only for standardized non-core activities but also for those which add more value to the firm, such as R&D, has driven some firms to outsource some of these activities to these locations (Lieberman, 2004; Maskell et al., 2007; Patel & Vega, 1999; Subramaniam & Venkatraman, 2001; UNCTAD, 2005), as this implies the possibility of significant savings on labor costs. As a consequence, we expect that the more importance is given to the search for a provider able to perform the R&D service more efficiently than the firm owing to its lower labor cost as a reason for outsourcing, the more likely firms will be to outsource R&D services to providers located in developing economies, as is the case with other activities such as manufacturing. Thus, we predict that,

Hypothesis 4. Conditional on the firm having decided to outsource to an offshore provider, the more important lower cost- seeking is as a motive for outsourcing, the more likely the R&D service is to be located in a developing economy.

2.2.2. R&D service attributes: the role of tacit knowledge and technological uncertainty

Previous works on offshoring highlights that the decision of where to locate a specific offshore activity is also dependent on the attributes of the task being offshored (Doh et al., 2009; Graf & Mudambi, 2005; Hätönen, 2009). In a similar vein, it has been argued that the option of outsourcing certain stages of business processes and offshoring parts of the value chain within firms to low-wage locations depends crucially on how processes are ‘embedded’ (Grote & Täube, 2007). In this sense, although previous studies have tested how specific service attributes affect the R&D outsourcing decision, they were focused on captive offshoring decisions (Cantwell & Santangelo, 1999; Doh, 2009). Thus, to the best of our knowledge, there is hardly any examination on how these service attributes influence the decision to outsource them to a particular offshore location. Therefore, through the combination of transaction cost theory and the resource-based view insights, we will take into account previous findings analyzing transaction factors influencing R&D outsourcing decisions and extend them to the international context. Specifically, we take two service attributes into account which have been found to be especially relevant when deciding either to outsource innovation activities or where to locate them: (i) the extent to which tacit knowledge is required to perform the service and (ii) the degree of technological uncertainty surrounding the activity.

2.2.2.1. The extent of tacit knowledge.

The degree of tacitness of the knowledge being transferred is considered as a factor hindering research and technology transfer (Howells, 1996). Tacit and specialized components of technological knowledge require costly person-to-person contact to transfer Teece (1977) and thus it will influence the firm’s propensity to outsource the service to a particular offshore location. This is the case because tacit knowledge is difficult to articulate, codify and transfer (Kogut & Zander, 1993) and, when outsourcing offshore, the transfer of this knowledge is more difficult owing to the different national cultures of the client and the supplier (Madhok, 1997). As a consequence, we expect these difficulties to be even more critical when outsourcing to offshore providers in developing economies, as the firms’ capability of efficiently transferring this tacit knowledge required to perform the service will be reduced owing to institutional differences, cultural distance, and communication costs (Teece, 1986). It has been found that services of a routinely and repetitive nature are more likely to be offshored to countries with lower wages (Doh et al., 2009). Obviously, a company willing to effectively transfer tacit knowledge to an outsourcing firm should dedicate time and effort to do this transfer, but by doing so it could be facilitating undesired knowledge transfers that might end up revealing valuable information to a provider performing activities directly related to the client’s core business, and thus it may imply a potentially risky upgrading of the provider’s technological competence (Arruñada & Vazquez, 2006; Larsson, Bengtsson, Henriksson, & Sparks, 1998). Therefore, we predict that:

Hypothesis5. Conditional on the firm having decided to outsource to an offshore provider, the more tacit the R&D service, the less likely it is to be located in a developing economy.

2.2.2.2. Technological uncertainty.

Technological change may have an important effect on the decision to internalize or outsource a particular activity, thus reducing the probability of outsourcing it to a particular location. Internalizing activities under conditions of rapid technological change impose inflexibility precisely when flexibility is most needed (Poppo & Zenger, 1998). In fact, literature analyzing strategic technology partnering has found that, whenever firms need quick responses to changes in technological leadership, non-equity agreements are preferred to joint ventures because they provide firms with greater strategic flexibility (Osborn & Baughn, 1990). Specifically, previous research has shown that greater use of outsourcing may deliver more flexibility, which may help firms to respond quickly to unanticipated threats and market opportunities (Hitt et al., 1998). Due to the fact that investments in technology are often quite specialized, rapid technological change may increase the likelihood of technological investments in knowledge and routines being rendered obsolete (Balakrishnan & Wernerfelt, 1986).

Thus, despite there being no empirical evidence on this issue, based on this previous literature together with the main motivations driving firms to outsource R&D services offshore, we expect that the outsourcing decision for services characterized by a high level of technological uncertainty will be largely driven by the need to access specialized providers with the resources and capabilities required to perform them at a particular time (i.e. having the most appropriate skill set), and not so much by the need to reduce costs (Poppo & Zenger, 1998). Therefore, we expect the level of technological uncertainty surrounding the R&D service to have a negative effect on the probability of a firm outsourcing it to offshore providers in developing economy usually characterized by a less developed technological and institutional infrastructure. This leads to our final hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6. Conditional on the firm having decided to outsource to an offshore provider, the greater the technological uncertainty surrounding the R&D service, the less likely it is to be located in a developing economy.

3. Data and methods

3.1. Research setting and data

We obtained data on R&D outsourcing agreements through a mail survey conducted on a sample of firms competing in R&D- intensive industries. The targeted population was made of companies with headquarters in the U.S. and the European Union (EU), with more than 100 employees, and whose two-digit SIC code was one of the five defined in the OECD classification of technology-intensive industries: (28) chemicals and allied products, (35) transportation equipment, (36) computers and electronics, (37) industrial machinery, and (38) analysis and measurement equipment. As mentioned above, efficient management of R&D plays a crucial role in the competitive strategy of these industries, so we expect these firms to make efforts to achieve superior efficiency in their R&D outsourcing agreements worldwide. We stratified the sample according to industry and firm size to insure external validity, using both domestic and international versions of the Dun & Bradstreet Million Dollar Database. Using these criteria, we obtained a list of 3529 U.S. firms and 3375 EU firms. From these lists, we randomly selected stratified samples of 2000 firms from the U.S. and 2000 from the EU, taking into account home country, industry and firm size.

We developed the survey instrument in several stages. Firstly, to understand better the R&D outsourcing phenomenon and to develop a more comprehensive questionnaire, we conducted interviews with the heads of technology and innovation of a large US-based multinational company both at the headquarters and at the subsidiary level. Secondly, we reviewed the literature extensively to identify relevant scale items for the concepts we wanted to measure. Finally, to avoid misunderstandings due to the international nature of the targeted population, the questionnaire was pre-tested on seven R&D managers working for different companies located in different countries, who indicated which survey items could be confusing and how to redefine them in order to avoid misinterpretations. Furthermore, the questionnaire was sent in one of five languages: English, French, Italian, Spanish, and German.6 Given the different sizes and industries included in our targeted population, the questionnaire was mailed to the firm’s chief executive officer (CEO) along with a request to pass it on to the head of R&D or technology if desired. The returned questionnaires were filled out by senior managers, namely: CEOs, VPs, heads of R&D or heads of technology or engineering departments. We followed the principles of the Total Design Method developed by Dillman (1978) which has been generally considered as the standard for mail surveys in the social sciences. This method is aimed at convincing respondents on the importance of the problem being analyzed, and thus that their help is needed to find a solution. A total of 105 completed questionnaires were received from the first mailing in July 2006. A second mailing was sent three months later and an additional 33 questionnaires were received, 303 mailings being returned as undeliverable. After a telephone follow-up process, we obtained a final sample of 182 usable responses (81 for the U.S. and 101 for the EU). After excluding the undeliverable addresses, our response rates were 4.5% for the U.S. and 5.3% for the EU. Despite the low response rate, the 182 responses obtained are representative of the spectrum of firms in terms of industry, country of origin, and firm size (see Table A1 in the Appendix A for the distribution of the mailed questionnaires and the responses). Besides this, we compared the responses from the first mailing with those from the second but found no significant differences at the 95% confidence level between early and late respondents in terms of all the variables used in the study. We also run analyses to test whether there were differences in terms of country of origin, firm size, or industry between the respondents and non-respondents, but again, not significant differences were found. We thus conclude that a significant non-respondent bias is unlikely.

We asked firms to indicate which R&D service activities they were outsourcing from a comprehensive list of twelve, and where in the world they were doing so. After making an exhaustive literature review of different sources on innovation and a review of business and statistical reports on R&D and websites from technological firms as well as those from specialized providers offering R&D services, we managed to identify a list of different R&D services or stages that could potentially be outsourced by technology- intensive firms. However, given that our aim was to obtain an exhaustive list of the categories of R&D services that could be outsourced by any of the technology sectors comprising the sample of this study, it can be expected that some services will be more applicable to some industries than others. Nevertheless, in order to tackle this issue, we have included applications specific to certain industries in the service typology. This final list was revised by a consulting firm and several R&D managers who helped us to refine our typology of R&D services. After their reviews, the R&D services identified were the following: basic or fundamental research, applied or experimental research, development of new products or new or improved processes, product design, design of technology processes and engineering systems, architectural services, software development, scientific and technical support consulting services, software implementation services, and testing and analysis services. We found that 108 of the 182 firms outsource at least one of the R&D services listed (60% of our sample).7 We asked these companies for more detailed information about the service being outsourced or, in those cases in which more than one service was outsourced, about the most representative service (i.e. in terms of resources and volume contracted). By focusing on these agreements, we were able to analyze the location and attributes of the most representative R&D outsourcing agreement for each firm more precisely. Missing data on some of the variables reduced the sample from 182 to 173 usable questionnaires.

Due to the fact that our dependent and some independent variables were obtained from the same survey instrument, our results could have been affected by common-method bias. In order to deal with this issue, we used the procedural remedies related to questionnaire design suggested by Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, and Podsakoff (2003), and we performed Harman’s single-factor test (Harman, 1967), which suggested no evidence of common-method bias.

3.2. Method of analysis and measures

This study investigates both the firms’ propensity to establish R&D outsourcing agreements offshore compared to other organizational options, and the likelihood of locating these agreements in developing economies instead of developed ones. Thus, two statistical methods, a multinomial probit regression, and a two-stage probit model were used to test the hypotheses. Our approach was to start by estimating a multinomial probit model for analyzing the firms’ choice of R&D outsourcing strategy. Then, to assess and correct for self-selection when analyzing the probability of where to locate offshore, we estimated a two-stage probit model corrected for sample selection (i.e. for the probability of the firm choosing an R&D offshore outsourcing strategy in the multinomial probit model). We then implemented this Heckman two-stage probit model in STATA, using the HECKPROB procedure in which both the first-stage and the second-stage are probit models (Heckman, 1978, 1979).

3.2.1. The decision of whether or not to outsource R&D services offshore

In order to estimate a model with multiple discrete outcomes, we used a multinomial probit model. As in multinomial logit models, in multinomial probit, the estimates of coefficients for independent variables measure the effect of the variation of the independent variable on the relative probability of the dependent variable taking a particular value in relation to the probability of it taking another value that is used as reference. The main advantage of using the multinomial probit instead of the logit is that this model allows error terms to be correlated across alternatives, thereby permitting it to circumvent the dilemma of the independence of irrelevant alternatives present in the multinomial logit model (Kennedy, 1998).

3.2.1.1. Dependent variable.

R&D OUTSOURCING STRATEGY accounts for the organizational and geographical dimension of firms’ R&D outsourcing practices. In particular, this dependent variable equals “0” if the firm does not outsource R&D services and it neither has captive R&D centers offshore, “1” if the firm does not outsource R&D services but has captive R&D centers offshore, “2” if the firm does outsource R&D services but only domestically, “3” if the firm does outsource some R&D services offshore but its main outsourcing agreement is located at the domestic market, and “4” if the firm does outsource R&D services offshore and besides its main outsourcing agreement is located offshore. Of the 173 firms in our sample, 48 firms took a value of “0”, 26 firms a value of “1”, 33 firms a value of “2”, 29 firms a value of “3” and finally 37 firms took a value of “4”.

3.2.1.2. Independent variables.

As an indicator of the firm’s technological resources and capabilities we introduced two different measures. One input variable (R&D INTENSITY log) was used as an indication of the firm’s effort in terms of R&D. We asked the respondent to estimate the firm percentage of R&D investment over sales. This variable was logged. Second, as an output measure of the firm’s accumulation degree of technological capabilities (PATENTS), we used the number of patents assigned to the firm until the end of 2006, as recorded by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (UPSTO). As experience and capabilities are developed and accumulated over time, we accounted for the complete track record of patents assigned to the firm. Patent data have also been used in previous studies to measure the technological capabilities of firms in high-technology industries (Bachmann, 1998; Praest, 1998; Tallman & Phene, 2007).8 To assess the firm’s overall international experience, we created the variable (MULTINATIONALITY), which counts the number of international wholly-owned subsidiaries possessed by the firm.

We also introduced some variables to control the heterogeneity of firms. To assess the degree of internationalization of firm’s sales, we introduced the percentage of firm’s sales being international (INTERNATIONAL SALES). To control the firm size, we used the logarithm of the firm’s sales during 2005 in dollars (FIRM SIZE). We also ran models using the number of employees as an alternative measure of firm size, and we obtained comparable results. We created a dummy variable (EU FIRM) coded one for firms founded in the European Union, and coded zero for the US. Finally, we introduced the following industry dummies: SIC 28 (Chemicals), SIC 35 (Transportation Equipment), SIC 36 (Electronics), SIC 37 (Machinery) and SIC 38 (Measurement Equipment). SIC 38 acted as the reference category.

Table 1 shows correlations and descriptive statistics for all the variables used in the first-stage model.

3.2.2. The decision of where to outsource R&D services offshore: developing versus developed countries

In order to analyze firms’ probability of offshore outsourcing R&D services to a provider located in a developing economy instead of in a developed one, we used a two-stage probit model. The aim of this probit was to assess and correct for self-selection (i.e. we control for the firms’ probability of offshore outsourcing R&D services, that is the firms’ probability to choose strategy number 4 in the multinomial probit model compared to the rest of sourcing alternatives). To do so, we recoded the dependent variable in the multinomial probit model as taken a value of one for those firms who indicated being outsourcing R&D services offshore and whose main outsourcing agreements were located offshore.

3.2.2.1. Stage 1: R&D offshore outsourcing decision.

The dependent variable in this first-stage probit model (R&D OFFSHORE OUTSOURCING) takes a value of one for those firms in category 4 in the multinomial probit model, that is, those who indicated being outsourcing R&D services offshore and besides their main outsourcing agreements were located offshore, and takes a value of zero otherwise.

The independent variables included in this first-stage probit model are the same as the ones used in the multinomial probit model: PATENTS, R&D INTENSITY, MULTINATIONALITY, INTERNATIONAL SALES, FIRM SIZE, and EU FIRM.9

3.2.2.2. Stage 2: R&D offshore location decision.

Our dependent variable in this second-stage probit model (DEVELOPING LOCATION) equals “1” if the main provider for the R&D service outsourced is located offshore in a developing economy, and “0” if the provider is located offshore but in a developed economy. Within these 37 offshore outsourcing agreements, 17 were located in a developing economy and 20 in a developed one.10

To account for the motivation for outsourcing an R&D service, we used two different items within the questionnaire.11 Firstly, we measured the need to access specialized providers (KNOWLEDGE-SEEKING), asking the respondent to evaluate the importance of “Lack of skilled personnel within the company” as a reason for outsourcing the R&D service from 1 (very low) to 5 (very high) on a Likert scale. Secondly, to measure the need to reduce costs (LOW LABOR COST-SEEKING), the questionnaire asked the respondent to evaluate the importance of “Cutting labor costs” as a reason for outsourcing the R&D service on a Likert scale from 1 (very low) to 5 (very high). In relation to the attributes of the R&D service, we proxied the extent to which tacit knowledge was implicit in the service being outsourced (TACITNESS). We used three items adapted from Kogut and Zander’s (1993) work, and asked the respondent to indicate his or her level of agreement with three statements related to the attributes of the R&D service they were outsourcing. Our inter-item reliability was also very high (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.823) so we combined these three items to represent our construct: (1) it is difficult for third parties to understand the company know-how related to this service, (2) it is difficult for third parties to copy or imitate the abilities or technological knowledge required to perform the service and (3) effective transfer of company know-how to perform this service requires a high level of frequent interaction with company personnel. Finally, we created a variable (TECHNOLOGICAL UNCERTAINTY) in order to assess the level of technological uncertainty surrounding the service. We asked the respondent to indicate his or her level of agreement from 1 to 5 with two statements adopted from Poppo and Zenger (1998) regarding the attributes of the R&D service they were outsourcing: (1) the skills required to perform the service are subject to frequent change and (2) the optimal configuration of hardware and software required to perform this service is subject to frequent change (Cronbach’s alpha=0.79).

We also included several control variables. Given that the previous literature also signaled process improvement as one of the main motives for outsourcing (Graf & Mudambi, 2005), we introduced a variable in order to control for this third motive for outsourcing (PROCESS IMPROVEMENT). In order to develop this measure, we asked the respondent to rank the level of importance of the following factors in the decision to outsource the R&D service on a Likert scale from 1 to 5: (1) reduction of time taken from product development to sales (‘time-to-market’), (2) cost reduction achieved through the consolidation of certain activities at specialized centers, (3) increase of operational flexibility and (4) reorientation of company efforts and resources to core activities. As the inter-item reliability was high (Cronbach’s alpha=0.754), we combined these four items to represent our construct. Furthermore, in relation to the R&D service being outsourced, we controlled for the level of difficulty in measuring worker performance (MEASUREMENT) as it might have an effect on the outsourcing location decision. We asked the respondent to indicate his or her level of agreement with the following statement on a Likert scale from 1 to 5: “It is difficult to measure the collective performance of those individuals who perform this service.” This single-item measure was adapted from Poppo and Zenger (1998) and it is consistent with previous work (Anderson & Schmittlein, 1984). In order to assess the firm’s international captive R&D experience in developing economies (CAPTIVE R&D IN DEVELOPING ECONOMIES), we introduced a dummy variable valued one if the firm owned subsidiaries performing R&D activities located in non-OECD countries, and zero otherwise. To assess the firm’s international captive R&D experience in developed economies (CAPTIVE R&D IN DEVELOPED ECONOMIES) we introduced a dummy variable that took the value of one if the firm owned subsidiaries performing R&D activities located in OECD countries, and zero otherwise. Finally, like in the first-stage, we also introduced the variable PATENTS to control for the firms’ accumulation of technological resources and capabilities.

Table 2 shows correlations and descriptive statistics for all the variables used in the second-stage probit model. No high correlations were observed.

Table 2 shows correlations and descriptive statistics for all the variables used in the second-stage probit model. No high correlations were observed.

4. Results

Table 3 reports the results from our multinomial probit regressions modeling the decision to outsource offshore, and Table 4 reports the results from the second-stage probit regression modeling the choice between suppliers located in developing versus developed countries corrected for endogeneity. Specifically, the tables show the value of the estimated coefficients, their robust standard errors and an indication of the significance level for each model. The models run reached significance levels below 0.001, as shown by the chi-squared values. Thus, the null hypothesis that all estimated coefficients are equal to zero is rejected in all cases.

Multinomial probit results predicting the choice of R&D sourcing strategy (reference group: neither R&D services outsourcing nor captive R&D centers offshore).

As can be seen in Table 3, the overall results support our hypotheses. According to our first hypothesis, PATENTS is positive and statistically significant in category number 4, so the progressive accumulation of technological resources and capabilities increases the probability of adopting an offshore outsourcing R&D strategy compared to conducting all of the R&D activities in-house in the home country. The same thing can be observed in categories 1 (firms doing R&D captive offshoring only) and 3 (firms undertaking domestic outsourcing and R&D captive offshoring). Interestingly, the only category in which PATENTS is non-significant is number 2, that is the one comprising those firms outsourcing R&D but only to domestic providers. This result suggests that having greater technological capabilities is an important driver when deciding to go offshore, either through the establishment of captive R&D centers of through outsourcing. Furthermore, when we analyzed the variable R&D INTENSITY aimed at measuring the technological resources a firm might have owing to its R&D efforts, we found that it is only statistically significant for those firms in category 4, that is, those outsourcing R&D services offshore. Thus, it seems that all else being equal, this result may suggest that firms that are more R&D-intensive are also more willing to search for R&D providers overseas in order to maintain their competitive advantage. While, another plausible explanation for these results is that they may be indicative of some reverse causality effect, as it could be the case that R&D outsourcing practices may lead to firms doing more internal R&D in order to keep up with and be able to integrate those external services. In addition, according to Hypothesis 2, the variable MULTINATIONALITY is positive and significant across all categories, which is indicative that those firms having more international experience are more likely not only to outsource offshore, but also to offshore R&D through captive centers or even to outsource to domestic providers, as compared to the probability of neither outsourcing nor having captive R&D centers offshore. To fully test Hypotheses 1 and 2 predicting a higher propensity to outsource offshore instead of other organizational alternatives, we also tested the significance of the coefficients associated to the R&D offshore outsourcing strategy (category “4” in the multinomial probit) and the rest of alternatives (“1” if the firm does not outsource R&D services but has captive R&D centers offshore; “2” if the firm does outsource R&D services but only domestically; and “3” if the firm does outsource some R&D services offshore, but its main outsourcing agreement is located at the domestic market). The appropriate statistic for this test is a t-statistic. These tests revealed that significant differences exist for PATENTS, R&D INTENSITY and MULTINATIONALITY (pb0.01) between firms following an R&D offshore outsourcing strategy and the rest of the alternatives.12 Therefore, we found that firms having more technological resources and those with more international experience show a higher propensity to outsource R&D services to offshore providers compared to other organizational options, as proposed in Hypotheses 1 and 2.

Regarding the control variables, when looking at the results of the INTERNATIONAL SALES variable, it is clear that the most active firms in international markets are more willing to outsource offshore, as the coefficient for this variable associated to the category number 4 (firms that outsource R&D offshore) is significantly higher than for the remaining categories (according to a t- test with pb0.05). Finally, with regard to the remaining control variables, our results suggest that U.S. firms are more likely to outsource R&D services offshore compared with those from the EU, according to the negative and significant effect of the variable EU FIRM when explaining the probability of offshore outsourcing as opposed to other sourcing strategies. Thus, it is interesting that, similarly to FDI, literature on R&D found that U.S. firms have been pioneers in the internationalization of their R&D activities compared with European or Japanese firms (Kuemmerle, 1999), we find that U.S. firms seem to be also pioneers in their decisions to outsource offshore stages within their R&D processes.

Regarding the hypotheses related to the firms’ motives for offshore outsourcing the R&D service, we find support for both Hypotheses 3a and 4. On the one hand, we find support for Hypotheses 3a, and not for 3b, as the variable KNOWLEDGE-SEEKING is negative and significant when explaining the probability of firms outsourcing R&D services to providers located in developing countries as opposed to developed ones. On the other hand, according to Hypothesis 4, the LOW LABOR COST-SEEKING variable is positive and highly significant when explaining the probability of outsourcing R&D services to developing countries compared with the probability of outsourcing them to developed economies. Thus, we do not find evidence of the fact that the more important is knowledge-seeking as a reason for outsourcing R&D services, the more likely they will be outsourced to providers in developing economies, as Hypothesis 3b proposed. However, it should be noted that these results may be indicative of the fact that R&D offshore outsourcing to developing economies is still in an early stage, as firms may evolve from seeking lower costs to knowledge-seeking objectives when deciding to outsource to developing locations (Jensen, 2009; Maskell et al., 2007). Indeed, taking into consideration the most representative R&D outsourcing agreements for the firms in our sample, when we analyze the average duration of the outsourcing relationships with the main provider for the R&D service, the results suggest that international R&D outsourcing is a rather novel business practice (see the ANOVA analysis in Table 5). Interestingly, we find that, on average, the outsourcing relationships with providers in the firm’s home country last substantially longer than those with providers located overseas, whilst international R&D outsourcing agreements with providers in developing countries enjoy the shortest relationships.

Finally, with regard to the hypotheses related to the effect of the R&D service attributes on the decision to outsource it to a provider located in a developing economy, both the variable TACITNESS and the variable TECHNOLOGICAL UNCERTAINTY display negative and statistically significant coefficients, which support Hypotheses 5 and 6 respectively. We analyze the causes and consequences of this preference for developed countries in the discussion.

Regarding the control variables, none of them appear to be significant when it comes to explaining the firm’s probability to outsource R&D services to a particular location.

5. Discussion and conclusion

The goal of this paper was to improve our understanding of the location determinants of R&D services offshore outsourcing agreements. In particular, we analyzed the factors driving technological firms to outsource R&D services overseas and the probability of locating those offshore outsourcing agreements in a developing country instead of in a developed one. The interesting element of this research question is that, despite the extant literature on offshoring of high-value adding functions and on R&D outsourcing in technology sectors, we find that there is no empirical examination on what drive technological firms to outsource R&D services to a particular offshore location. To the best of our knowledge, only a few studies have addressed this issue, and then mainly from a theoretical perspective (Contractor et al., 2010; Doh, 2005; Graf & Mudambi, 2005; Hätonen & Eriksson, 2009; Kedia & Mukherjee, 2009; Mudambi & Tallman, 2010) or case illustrations (Hätönen, 2009; Mudambi & Venzin, 2010), or just focused on captive offshoring (Demirbag & Glaister, 2010; Doh, 2009). Therefore, this study contributes to this previous literature by providing empirical evidence regarding how factors such as what is being outsourced and why, what kind of experience the firm has, and what influences the decision of where to locate R&D services outsourcing agreements. Our study places special emphasis on the fact that, in order to outsource overseas, some firm-specific capabilities are required, especially when offshoring to developing economies. The explicit consideration of these capabilities would thus help to explain inter-firm differences in the propensity to outsource R&D offshore.

With regard to the first question of whether or not to outsource R&D services offshore, our results show that this decision depends on firms’ characteristics such as their level of technological resources and firms’ international experience. Specifically, those firms having more technological resources are overall more likely to offshore their R&D, that is, not only through outsourcing but also through the establishment of captive centers. However, we find that firms establishing R&D outsourcing agreements offshore are not only those with greater technological resources, but also those that are more R&D intensive. Indeed, these firms are the ones that appear to be benefiting the most from this R&D global outsourcing market. In addition, results show that firms’ international experience plays an important role in these decisions, as those firms having more subsidiaries located overseas and, especially, those with a higher percentage of foreign sales seem to be more likely to offshore R&D not only through outsourcing but also through the establishment of captive centers. Therefore, when taken together, our findings suggest that, although both firms’ level of technological resources and international experience are important factors determining R&D offshoring decisions (captive and outsource offshoring), their influence appears to be greater in deciding to offshore R&D through outsourcing agreements. Indeed, previous research has found that technological capabilities increase both the probability of captive offshoring (Berry, 2006) and offshore outsourcing (Quinn & Hilmer, 1994). While, there are also available evidence regarding the role of a firm’s international experience both on captive offshoring (Berry, 2006; Belderbos, 2003; Odagiri & Yasuda, 1996) and offshore outsourcing (Mol et al., 2005). As well as there is recent evidence showing the important role of both capabilities and international involvement in order to decide to outsource R&D offshore (Bertrand & Mol, 2010). However, none of these studies have analyzed jointly the R&D captive offshoring and R&D outsource offshore decision. Focusing now on the importance of multinationality and international experience, our results highlight the importance of having a network of subsidiaries (Kogut & Kulatilaka, 1994) in order to outsource offshore. Therefore, a network of subsidiaries provides flexibility not only by the option to move activities across borders, but also because of the ease of outsourcing offshore. Nevertheless, international expertise is also important when selecting and monitoring offshore providers, as experience increases the firm’s ability to develop business relationships in different institutional environments. Thus, taking our first-stage results as a whole, it becomes clear that some firm-specific attributes related to governance capabilities (technological and international expertise) are important drivers in the decision to outsource offshore instead of relying on other organizational options, like in-house activities, domestic outsourcing, or captive offshoring.

Indeed, with regard to the second question of where to locate these R&D offshore outsourcing agreements offshore, results show that the likelihood of outsourcing an R&D service to a provider in a developing economy, as opposed to a developed one, increases: the less important is knowledge-seeking as a motive for outsourcing the R&D service, the more important is lower labor costs as a motive for outsourcing the R&D service and the less tacit and subject to technological uncertainty is the service being outsourced.

First, with regard to the influence of the firms’ motives for offshore outsourcing R&D, our results show that the main driver to outsource to developing economies is still their labor cost, while those firms outsourcing R&D for knowledge-seeking reasons seem to prefer developed locations. Therefore, although there are recent studies on offshoring arguing that firms are increasingly relocating innovation activities to developing countries motivated by the high-qualified workforce within these regions (Lewin et al., 2009; Manning et al., 2008), our study contributes to this literature by finding that in the specific case of R&D services, knowledge seeking do not lead to outsource offshore to developing economies. Despite this, we should note that this may not be the case for other services, and as international R&D outsourcing is a rather novel business practice, in the near future we could see a propensity to outsource from these countries. Besides, it should be taken into account that there is recent evidence suggesting that increasing commoditization of knowledge services opens up windows of opportunity for the development of new clusters in second-tier locations (Manning, Ricart, Rosatti Rique, & Lewin, 2011). Therefore, one limitation of this study is that our findings may be context-specific. This is, however, inevitable when one tries to disentangle this phenomenon and move beyond the aggregate analysis within this topic. Thus, from a dynamic perspective, it can be expected that, as firms gain experience through outsourcing in developing countries and, as a result of these practices, providers within these regions develop greater technological skills, firms may evolve from seeking lower costs to knowledge-seeking objectives when deciding to outsource to developing locations (Dossani & Kenney, 2003; Jensen, 2009; Maskell et al., 2007; Ricart et al., 2011). In other words, this propensity to outsource high-value R&D research services will increase as firms from emerging markets accelerate the catching-up process whereby they are reducing the competitive gap against established MNEs (Guillen & Garcia-Canal, 2009).

Second, when analyzing the influence of what is being outsourced in the decision of where to locate the R&D offshore outsourcing agreement, we observed the significance of both the degree of tacitness of the knowledge required to perform the R&D service, and the degree of technological uncertainty surrounding the service. In line with previous research arguing that the degree of tacitness of the knowledge transferred hinders research and technology transfer (Howells, 1996; Howells et al., 2008), our study highlights the difficulty of effectively transferring tacit knowledge offshore as the institutional and cultural distance between the firm’s home country and that of the provider increases (Madhok, 1997; Teece, 1986). Our main contribution regarding this variable is to show that providers in developing economies are preferred for more commoditized activities, providing evidence in the R&D outsourcing field on how the degree of standardization diminishes the relevance of geographic distance (Demirbag & Glaister, 2010). Indeed, what we found is that much of the services outsourced to these regions are related to quite standardized software services, where Asian countries have low-cost pockets of expertise. Finally, we found that the more technological uncertainty there is surrounding the R&D service, the more likely the firm is to offshore outsource it to a provider in a developed country as opposed to a developing one. This result suggests that, for services characterized by frequent technological changes which may render human and capital technical investments obsolete, offshore outsourcing to providers in developed countries adds flexibility to the firm, since it offers the possibility of switching providers with different technological resources and capabilities as the need arises. Besides, it could be argued that under frequent technological change, outsourcing contracts are subject to renegotiation, which may lead to face a higher risk of opportunism if contracting with providers in a developing economy which are usually characterized with higher level of political instability or corruption (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2006). Therefore, whenever the resources and capabilities required to perform an activity may be subject to frequent change, it seems more convenient for technological firms to outsource to providers located in more stable developed economies.

Yet—similarly to the previously explained expected evolution from cost to value with respect to the motives driving firms to outsource to developing countries—from a dynamic perspective it can also be expected that the nature of what is being outsourced to these economies will vary towards more complex functions. This is because confidence and trust in the partner have been found to be a major constraint on the sourcing process (Howells et al., 2008). Therefore, it can be expected that, as the firms gain experience of doing business within these economies, the duration of the outsourcing relationships with providers in developing countries will increase and evolve towards more long-lasting and trustful relationships. Indeed, when asked about the performance achieved within these R&D outsourcing agreements with providers located in developing economies, firms within our sample claimed to be, on average, highly satisfied. However, they also indicated to be considering Asian countries, such as China or India, or Russia within Europe as the next regions where they were planning to increase their R&D outsourcing agreements. This fact may facilitate the transfer of more tacit and complex knowledge given that, as firms accumulate experience of contracting in these economies, the parties may learn to cooperate and can thus renegotiate more equitable and efficient contracts (Coltman, Bru, Perm-Ajchariyawong, Devinney, & Benito, 2009). Therefore, the results of these two variables related to uncertainty and complexity, whose influence have not been tested yet in the field of the location of R&D offshore outsourcing agreements, confirm that transaction costs are still the main deterrent to outsource offshore to developing economies. Taking all of our results as a whole, we can affirm that, in order to explain both the decision to outsource offshore and its preferred location, we need to take into account the need for external resources, the firm’s governance capabilities and the transaction costs associated to the outsourcing relationship.

5.1. Limitations and future research

This paper is not without its limitations. A more fine-grained study could be developed if we knew the volume outsourced as a percentage of the total budget allocated to the R&D service and of the total R&D outsourcing budget. Even though our respondent firms are representative of the population by country of origin, industry, and firm size, we obtained a low response rate, so our results should be treated with caution. This study could also be further developed by analyzing the type of outsourcing relationship—i.e. long-term versus short-term agreement—chosen by the firm depending on the R&D outsourcing location or type of R&D service being outsourced. Indeed, as stated by Doh et al. (2009), despite the important contributions of previous literature regarding these practices, past research focused largely on offshoring in the aggregate sometimes overlooking the diversity and complexity of offshore services activities and related location decisions geared toward specific offshoring functions. Even though, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first quantitative study addressing both whether and where to outsource R&D services offshore, it is very difficult to perfectly separate the two dimensions. In effect, these two decisions are closely interrelated, as depending on the firm and the activity being outsourced there is no general agreement regarding the sequence of outsourcing and offshoring decisions (this discussion has been highlighted, for instance, in Mudambi & Venzin, 2010). Unfortunately, as we have cross-sectional data, it is not possible for us to test the sequence of these decisions, but to control for the different combination of organizational options that can be followed by the firms. Thus, one limitation of our study is that although we have addressed whether and where to outsource offshore R&D, our analysis of the first decision does not attempt to fully explain firms’ organizational choices for R&D services, but to account for the endogeneity associated to any organizational choice.

In relation to the role of firms’ international experience in R&D offshore outsourcing decisions, our findings contribute to the literature by showing that firms with a higher level of international experience—regardless the location of the firms’ subsidiaries— are significantly more likely to outsource R&D services offshore compared to other organizational alternatives. This suggests that firm’s international involvement may help develop the required managerial capabilities to effectively identify capable providers offshore and manage and control those outsourcing agreements. However, the fact of having captive R&D experience in offshore developed or developing economies appears to have a non-significant effect on the preferred developed versus developing location for the agreements. This result may suggest that in some offshore locations captive R&D and outsourcing may act as substitutes rather than complements. Thus, one limitation of this study is that the way we measure the international experience of the firm might be an oversimplification—as due to the lack of more specific data we are not controlling for whether spillover effects occur between different foreign countries.

Therefore, further research overcoming these limitations and taking a longitudinal approach could facilitate a better understanding of the R&D offshore outsourcing phenomenon. In particular, it would be of great interest to gather longitudinal data so as to analyze the evolution of these offshore outsourcing agreements in terms of the volume and complexity of the R&D services being outsourced to specific offshore locations. In this sense, several directions for future research can be identified. From the perspective of the client firm, further research is encouraged so as to identify whether and under what circumstances or locations captive R&D and outsourcing may act as substitutes or as complements when crafting a firms’ technological strategy. From the perspective of the supplier, further research deserves the analyses of what governance mechanisms or managerial practices could be developed in order to try to capture more advanced technological services over time. From the perspective of governments, future research should build on how to attract R&D investments from foreign firms, while at the same time developing policies so as to encourage local firms not to offshore. Thus, our study could be also extended by analyzing how government R&D investment programs may affect private R&D offshore outsourcing location preferences. In this sense, previous studies have shown the effect of government R&D expenditures and attraction programs on private R&D investments and productivity (Levy & Terleckyj, 1983), as well as the fiscal and non-fiscal instruments that not only governments in developed economies but also those from developing ones may employ to stimulate investments in R&D (Mani, 2004). Therefore, from an economic policy perspective, extending previous research on the effect of these programs on attracting R&D outsourcing practices would be of great interest. Specifically, the focus should be on analyzing what government policies fostering greater innovation and technology development may help to attract R&D outsourcing contracts from foreign firms, as well as to help to avoid local firms outsourcing offshore (Lieberman, 2004).

5.2. Managerial implications